Last week, I found a Ferrero Rocher wrapper tucked inside a library book. It felt like a small interruption, a trace of someone else’s moment. I love this residue sometimes found in library books: the folded corners of pages, the underlined passages of text. I began thinking about the idea of found ephemera and the role it plays in my work. The phrase lingered from my art education, and when I looked it up later, I was reminded that it refers to transitory, paper based objects not intended to last: postcards, tickets, flyers, photographs. The word itself comes from the Greek ephēmeros, meaning lasting only a day.

I had just finished a monotype of my son holding the instant print camera he received for Christmas. In the 35mm photograph I worked from, he is bare-chested, looking over his shoulder, out of the window. The pictures from his little camera, ticket-sized and fragile, feel inherently disposable. I like holding them, a cheap version of a Polaroid. I suggested we make a scrapbook, but instead they drift through the house. I find them under the sofa, on the stairs, behind doors. I move from room to room like Hansel and Gretel, gathering the trail, slipping them into a white envelope.

Around the same time, I overheard a conversation in the library between a small boy and his minder.

Can I see that picture you just took?

No, I sent it. It’s gone.

But can I see it?

No. It’s disappeared.

The boy looked confused. “You don’t understand,” the minder said. I imagined the image travelling instantly elsewhere, to a mother’s phone, into an app, present and absent at once.

There is a shared disposability in these moments. Both involve children encountering, early on, the strange impermanence of images: those that are fragile, misplaced, deleted, or vanish into data heaven. Some images, however, linger. Thinking about this alongside Susan Sontag’s writing on photography, it becomes difficult to comprehend the sheer proliferation of images. There are simply too many. All I know is that I am drawn to the discarded ones, like a magpie. I would agree, I am an addict of sorts. As Sontag writes, “Industrial societies turn their citizens into image junkies” (On Photography, 1977).

Much of my work is mined from old photographs and found imagery. I have a large plastic bag, rescued from the bin by force of sentiment, filled with old photographs and school reports. It has travelled with me from Bournemouth to London, to Kent, to Dublin. I am also drawn to images in old copies of National Geographic, though only certain photographs call out, insisting on attention. The downside of this tendency to collect printed materials is that I find it hard to look at things neutrally. I am always on, searching for something that sticks, and when I find it, I cling to it like a life raft. The picture confirms something. I just don’t know what that something is.

When I first moved to Dublin, I took on a portrait commission from a family friend. It seemed practical, something I could do while the children slept, and I had painted portraits of loved ones before. Instead, I found myself sitting for hours with the photograph of the child I was meant to depict, unable to translate his likeness into paint. I kept wondering why the photograph wasn’t enough. What was being asked of me felt heavier than representation. There is a significance, a cachet, attached to a portrait made by hand, and that pressure settled with me uneasily: the prestige of a painting, its weighty permanence.

Around the same time, I became aware of a growing insistence on slowness. In 2015, when I first moved to the city, I brought with me a book called Slow Dublin, hoping to learn the place from a different perspective. Since then, I’ve noticed more and more books with ‘slow’ in the title: Slow Painting by Helen Westgeest (2020), another of the same name by Hettie Judah (2019), and an exhibition titled Slow Image that opened last week at The Library Project. My restless mind can’t help wondering, how slow is slow enough?

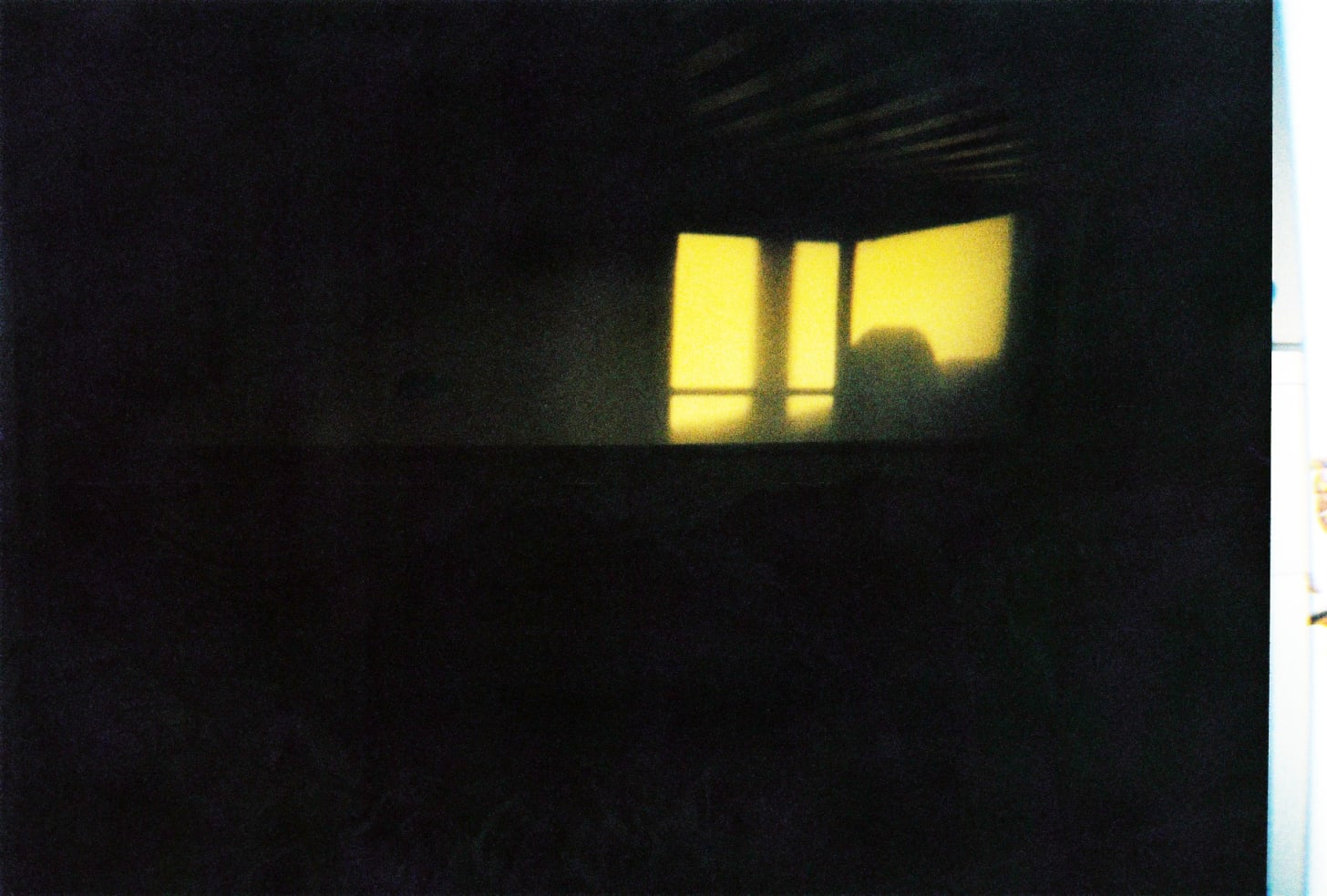

Recently, on the Research Ethics module I am studying, I mentioned that sometimes I paint images that feel too intimate to share in any other way. I noticed the lecturer pause. Since then, I’ve been circling the question of what this says about the photograph itself, or about the experience of taking a photograph. I feel a loss. I’ve stepped out of the experience to capture it. What does it mean to paint a photograph of this kind, to place a veil between myself and the subject, to reduce the exposure, both to me and to those whose images I hold? Or does painting bring me closer to the captured moment and its afterlife?

I don’t have any answers to these questions. I find myself second-guessing, drawn, as ever, to what is found, discarded, altered, and held at a distance.

A couple of recently read artist writings related to these questions:

In general, I became enamored with offset printing and began sporadically collecting posters for art exhibitions and pop concerts. I was intrigued by the ephemerality of these artifacts, excited by the feeling of having singled out something that would otherwise have been discarded. The moment a picture comes through the processing machine it begins to deteriorate. Again: permanence is impossible. Entropy is our condition. To show the fragility of a print is to show its strength. The concepts of permanence, impermanence, materiality, authenticity, value, and fragility are central to my practice. Underpinning it all is a profound appreciation for the potential of this simple piece of paper: an old lithograph, a concert poster, a magazine page, a freshly ejected photocopy. It all leaves a lasting impression.

Wolfgang Tillmans, On Paper, 2022

I enjoyed this short text, even though it is quite technical at times. Tillmans studied at Bournemouth and Poole Arts Institute, where I also studied after school between 2000 and 2002. See more here.

My final show as a photographer was called Constellations. It opened ten years ago this week at @circuitgallery, in the very building where I now have my studio. It marked the first time I created a body of work drawn from my own domestic life, my parents, my kids. It was pretty straightforward, whereas most of my earlier photo projects had been mitigated by some cleverness, a wink, a distance. This was earnest work, and it was deeply satisfying.

So satisfying, in fact, that when the show came down, I felt I was done, like there was nothing else for me to say with photography. I went back into the studio, spinning my wheels, and decided I needed to start all over. That moment led me to painting.

I was never a very contented photographer. I don’t love being out in the world with a camera. I didn’t like the gear or the knowledge required to use it. I don’t like sitting behind a computer, thinking thoughts. When I started painting, it was the process that hooked me. I like making things. My best days in the studio are when I’m not even there. I’ve disappeared into a painting.

Nancy Friedland, Instagram post from January 6, 2026

The exhibition mentioned which opened yesterday at the Library Project in Dublin:

Slow Image, curated by Noémie Cursoux with the support of Black Church Print Studio. Slow Image brings together practices that explore and question the materiality of the image in relation to contemporary visual culture. The title of this exhibition is inspired by Helen Westgeest’s publication Slow Painting, in which the author reflects on handmade image making as a counterpoint to the rapid, consumable imagery of our media saturated world. Text from press release.

Leave a comment